Too Many Ways to Die

Man Full of Trouble (Chapter Four): Great Sex; From Liverpool; This Bar Doesn't Exist; Born During the Worst Parts of the Bible; Trouble in Kansas

After a pause due to the holidays and heartbreaking wildfires here in L.A. … this is the fourth installment of my pulp non-fiction gangster memoir, Man Full of Trouble, detailing the rise and fall of the criminal who killed a family member 100 years ago. I’ll be sharing chapters through March 2025. (Here are Chapters One, Two and Three.) Comments and questions are welcome; huge thanks to the paying subscribers funding this book.

December 11, 2018

One hundred and two years ago, at this very location, my great-grandparents had sex.

This location being 106 Kenilworth Street in South Philly—a stone’s throw from the frosty Delaware River. I’m a little tipsy now as I stare up at the tall, narrow rowhome, trying to imagine it.

No… not the sex. I’m not going to speculate on the specifics of my grandfather’s conception. That’s none of my business, and none of yours.

But I do wonder about the logistics.

According to the 1920 census, there were 19 human beings living in this 2,073-square-foot rowhome built in 1860. My grandpop Walter was the baby of the family, joining nine siblings (Helen, John, Marta, Leona, Alexander, Catharine, Charles, Bernard and Stella). If my great-grandparents had decided to skip relations that night—and with nine kids running around the house, who could blame them?—then POOF. You’d be reading something else right now.

I wouldn’t exist.

In many ways, however… I don’t exist. This part of my family tree is obscure. We’re all Swierczynskis, but I don’t know much about them or their descendants. My grandparents divorced when my father was young; I grew up visiting my grandmother’s Italian side of the family (the Perillis). Diving into Swierczynski family history makes me feel like I’m picking up a mystery novel around Chapter 43 and struggling to puzzle out the characters and backstories.

As I try to wrap my head around my ancestors’ life here more than a century ago, I realize all I have are fossils.

Fossils are traces of once-living organisms. Scientists analyze them and use all kinds of clever techniques to tell the stories of long-extinct creatures. I’m not a scientist, and not especially clever. I make do with the fossils I’ve managed to unearth.

This means immigration papers and census reports and draft cards and newspaper clippings and death certificates. But all of these were created by human beings, who are prone to make mistakes. Dates are routinely mangled. Handwriting might be sloppy. The name “Swierczynski” is almost never spelled correctly.

So like any good detective, I need to go back and start at the beginning.

December 27, 2014

My wife and son have a youth choir event at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, leaving the Daughter and I with a couple of hours to kill. I drag her to Southwark for some historical research, just like we did back in April.

This time we head to the Delaware River to the former location of the Washington Avenue Immigration Station. More than one million people passed through this station at Pier 53 on their way to Philadelphia or some other destination. This was our Ellis Island. The station closed in 1915 (just after my maternal great-grandfather made it through the gates). But 99 years later, the Mayor of Philadelphia dedicated the former pier as an ecological park, including a spiral-staircase observation deck called “Land Buoy,” created by artist Jody Pinto. I’ve been meaning to check it out.

Evie agrees to go with me, so long as there is some kind of dessert at the end of our visit. (She’s shrewd that way.)

We take in the ruins of Pier 53. I tell Evie this is where it all started for the Swierczynski Family in America. She doesn’t ask me for specific details; this isn’t her way. She just lets me ramble.

Thing is, the specific details are in flux.

Three months before our visit, I emailed Susan McAninley at The Pier 53 Project, which was actively compiling a list of all immigrants who passed through the station. If your ancestor matched, you were invited to tell their story.

You also received a commemorative passenger tag and a t-shirt.

I shared my great-grandfather’s details with Susan, who responded:

“I’ve been researching your family and have come to a wall with Anthony John. There are immigration dates floating around: December 1901 and December 1902. He did not come here in 1901; no record of him on the passenger list. The December 1902 passenger list from the Noordland is missing … I understand there’s a lot of information available through some of the local Polish churches and clubs, and you have provided the first occasion I’ve had to investigate anyone of Polish origin in Southwark; I can’t seem to find the right people. Hope you have better luck than me … At some point I hope you will become a member of the Pier Group and get a t-shirt as an official descendant.”

By the time Evie and I visited the ruins of Pier 53, I was still trying to earn my t-shirt.

But according to my great-grandfather’s immigration papers, he and his wife and two children arrived at Pier 53 in 1902 via the Noordland. So I’m going to go with that, unless I find compelling evidence to the contrary.

I spent a few days of research tracing the Noordland’s journey from Liverpool (birthplace of my favorite writer, Clive Barker) all the way across the Atlantic. The ship departed on November 26, 1902. The journey was rough, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, with “tales of wild days and wilder nights at sea.” By December 8, my great-grandparents were able to catch sight of their new home, just off the coast of Delaware. They arrived at Pier 53 on December 10.

Standing here on their landing spot, I look toward Philadelphia, and wonder what the view was like then. I try to imagine their excitement and terror. I know nothing about their lives in Poland, but I’m sure the City of Brotherly Love was a rude shock to this young family. Just six months after their arrival, Lincoln Steffens would publish his infamous “Shame of the Cities” piece in McClure’s Magazine that described Philadelphia as “corrupt and contented.”

I stare at the city, no idea that four years from now, I’ll wandering the streets of Southwark, drunk and grieving, trying to solve an impossible mystery.

Evie, meanwhile, stares at the exposed pilings of the former pier. I snap a picture. I don’t know what she’s thinking in that moment.

I wish I could ask her.

December 11, 2018 (continued)

I walk south on Front Street. Whatever warmth I had absorbed from Lucky’s was gone. The air was raw, biting. I had a vague idea about walking down to the ruins of Pier 53 again. But walking alone along the Philly waterfront in the dark, a few beers in me, would be an excellent way to get killed. This wasn’t my town anymore; my instincts were off.

The only logical thing to do would be to find another bar.

Partly for the warmth, partly for the booze. But also for the research. I was searching the former Southwark for any traces of what might have hung on since the 1910s, 20s or 30s. I suppose I had this fantasy about turning a corner and seeing some dive bar, mostly forgotten by the rest of the city. In this imaginary bar—which hasn’t seen a fresh coat of paint since Watergate—I’d pull up a stool and start a conversation with some impossibly ancient dude who remembers The Bad Old Days. Only reason he’s alive? He pickled his internal organs with Schmidt’s and cured his lungs with an endless series of Tareytons. And we’d get to talking and he’s say, what’s yer name again? No, your last name? Really? Say, I knew a guy with that last name…

But no such bar, nor old salt, presented themselves.

Instead, I have to piece together the world my grandfather, Walter Swierczynski, entered when he was born in late summer 1917. And let me tell you… he entered this plane of existence at one of the most fraught moments of the 20th Century. I know, I know; things aren’t so great in the early 21st, either. But you’ll see what I mean as I walk you through it.

A month after my grandfather was conceived, workers at Franklin Sugar (and nearby McCahan Sugar) went on strike. My great-grandfather Anthony John Swierczynski was a laborer at Franklin Sugar. Every day he’d put in his hours at the plant and then return home to 106 Kenilworth—a ridiculously short commute. If the sugar factory were a university, my family’s rowhome could have been considered on-campus housing.

So my great-grandfather was presumably among the strikers. What happened? Food prices had spiked. Many families couldn’t afford potatoes or parsnips, let alone meat. The workers were asking for ten cents more an hour (and the Lord’s Day off) to help makes ends meet.1

The companies, not giving a shit about any of that, hired strike-breakers.

On February 21, hundreds of women—inspired by similar protests in New York City—gathered at Moyamensing and Christian to demonstrate. By 5 p.m., forty of them were ready to take their complaints directly to City Hall. More than 250 cops showed up to disabuse them of that notion. Word spread quick, and hundreds of protesters—men, women and children—joined the original 40. This kicked off a two-hour battle where, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer:

“Bullets whizzed by the heads of the policemen as they crouched in the patrol wagons. There came another shower of shot, followed by bricks and other missiles. Policemen charged the rioters with drawn revolvers, firing volley after volley into their ranks and getting in return a shower of bullets, bricks and stones… Many of the women, children and men were badly bruised by the clubs of the police who showed no mercy and struck at all who came within their reach.”

Two hours later, one male protester had a bullet through his heart, and four others—including two cops—were “probably fatally injured.” The Inquirer called it “the most desperate and bloody riot which was occurred in Philadelphia for years.”

And it was only February.

On April 6, the United States declared war on Germany. That same day, the SS President Grant, a German vessel, is seized. (This was the same boat that carried by maternal great-grandmother to the U.S. a few years before.)

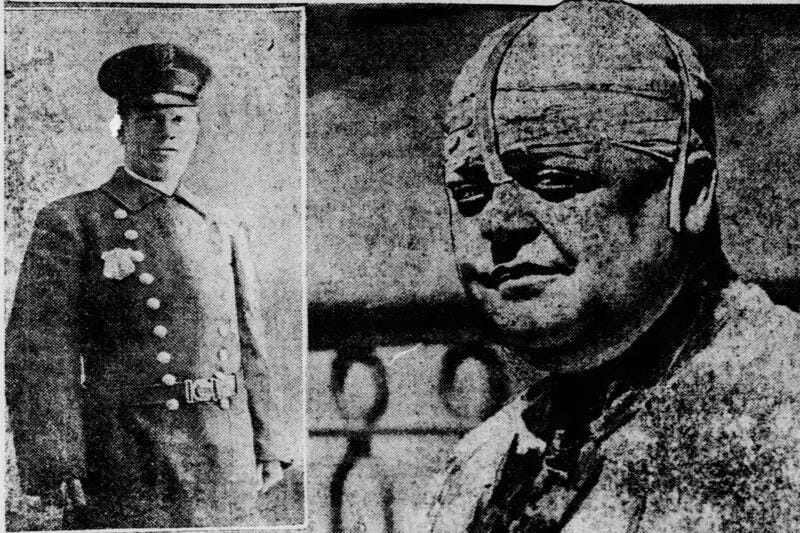

A week later, the City of Philadelphia decided to add 500 police officers to the force. Joseph T. Swierczynski, my grandfather’s much-older cousin, applied for duty and was sworn in by the end of the month. And just in time, too: his second child, Joseph, would be born that July.

On August, 10th, my grandfather Walter was born.

Two new babies in the Swierczynski family, just a few doors apart, in a city spinning out of control.

A month later was the infamous “Bloody Fifth” cop killing. “Fifth” meant the Fifth Ward, where my ancestors lived. Police officer George Eppley was murdered trying to protect city council candidate James A. Carey from a New York gang ("the “Frog Hollow Musketeers”) hired by the opposition to beat the living fuck out of him. The scandal would rock the city; Mayor Thomas Smith would be indicted for his role in the plot.

Four months later, when my grandfather was not quite five months old, temperatures in the city dropped below zero. After New Year’s Day 1918, they barely climbed out of the single digits. Pipes burst. Citizens snapped bones slipping on ice. An abundance of fires broke out; the fire department was exhausted from the volume of calls. To make matters worse: the coal bins were empty.

In those days, homes and businesses and schools and pretty much everything were heated by coal. (Can you imagine such a backward time?) The City of Philadelphia required 19,000 tons a day just to keep the basics running. The abnormally cold weather resulted in a “coal famine.” Rail cars would show up with only fifth of what had been ordered. The river wards were freezing. Even rich country clubs started to cut back on their coal consumption.

And the coal trains ran right down the middle of Washington Avenue, which was the southern border of Southwark. They carried tons of anthracite to at least 30 coal yards between Twenty-Fifth and Second. At the end of the avenue, right at the river’s edge, was the Pier 53 immigration station. For many newcomers, Washington Avenue was the first American street they saw. But it wasn’t paved with gold. Mostly likely, the immigrants saw a lot of coal dust.

Except in the final days of 1917, those trains rumbling along Washington Avenue were carrying fewer and fewer lumps of coal.

Just after New Year’s Day 1918, thousands of freezing residents took matters into their own hands and raided the idling coal cars all along Washington Avenue. Women and children climbed over the heads of police officers and ultimately seized over 150 tons of anthracite. The police mostly stood down. What were they going to do… beat up a bunch of freezing mothers and their skinny kids?

I wonder two things: was newly-minted police officer Joseph T. Swierczynski called in to help restore order? But also: did any of my family members take part in the riots? Did any of that stolen coal end up heating 106 Kenilworth?

This was the world my grandfather was born into: global chaos, corporate greed, civic corruption, food insecurity and a hostile climate. It was a miracle he was born; a miracle he survived.

But the biggest threat to his existence—and my own—emerged just two months later, in March 1918, thanks to a burning pile of shit somewhere in Kansas.

Special thanks to historian Ken Finkel, who wrote about the Sugar and Food riots in December 2020 installments of his excellent Philly History Blog.