Mass Casualty

Man Full of Trouble (Chapter Seven): Polish Wake; Grief in Bronze; A Godless Heathen Goes to Church; The Kangaroo and the Camel; A Slice of Pizza with the Dead

This is the seventh installment of my pulp non-fiction gangster memoir, Man Full of Trouble, detailing the rise and fall of the criminal who killed a family member 100 years ago. Comments and questions are always welcome; huge thanks to the paying subscribers funding this book.

Monday, March 24, 1919

Fallen police officer Joseph T. Swierczynski’s wake began at 4 p.m., according to the Evening Public Ledger, held inside his home at 120 Kenilworth Street.

The same home that just one week before was bustling with two little children — and a pair of young parents who had no idea what was coming for them.

The Ledger reported a steady stream of visitors until midnight. The next morning, Rev. Dr. John Godryz, of nearby St. Stanislaus parish, led a brief service before Joseph T.’s body was then carried to St. Stanislaus on Fitzwater Street, just a few blocks away, for a full requiem mass.

According to Google Maps, the distance is 0.2 miles — a 4-minute walk, mostly down Second Street, accompanied by the Philadelphia Police honor guard and band, with six patrolmen serving as pallbearers.

I’m sure my branch of the Swierczynski family tree (my grandfather and his nine surviving children) were present. But I wonder if my toddler grandfather was brought to the wake at 120 Kenilworth, or the requiem mass. Or if he retained any memories of this part of his life at all. This was already season of grief in the Swierczynski family; my baby grandfather had lost his mother and older sister to the influenza pandemic just five months before.

Joseph T. was interred at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, just outside the city.

His alleged killer, Anthony Zanghi, sat in prison.

Life moved on, as it stubbornly does.

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

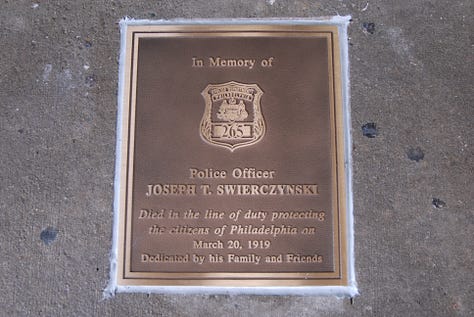

Eighty nine years later, the Philadelphia Police Department placed a memorial plaque in the very spot where Joseph T. bled out and died.

A police flag covered the freshly-installed bronze memorial as bagpipers played and highway patrol blocked off 800 and 900 Christian Street. Joseph T.’s descendants were ferried to the corner of 9th and Christian in limousines, greeted by the Police Commissioner, then directed to a row of metal chairs with gray padding facing Lorenzo’s Pizza.

Local disc jockey Bob Pantano opened the ceremony, and introduced Monsignor Michael McCulkin from Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul.

“May the almighty God grant us peace now and forever,” the Monsignor said. “Oh God by whose mercy your faithful find rest, bless this plaque with which we mark the place where our brother, officer Joseph Swierczynski’s life was taken from us, as he sought to protect his fellow citizens, your people, from the certain harm that faced them. May he have everlasting life in your peaceful presence forever. Amen.”

FOP President John McNesby took his place behind the podium.

“Eighty-nine years by all counts is a long time,” McNesby said. “Most, if not all people involved in his death — his widow, two sons, other immediate family members, the witnesses and officers he worked with, have left us. What of course remain are the memories, recollections, and written history that Joseph is a hero. Decisive, brave, able to face the danger that confronted him to do what was right. His resolute fearlessness, taking on armed men in the street, pursuing them to the place, a saloon. Then, at this location, where rather than face certain arrest, they cowardly attacked him from cover, is what brings us here today. In addition to the memories and recollections we have evidence. That evidence is not in the traditional sense, but in the presence of his extended family … A lot has changed in 89 years, but time can never change, time can never erase, what we know about the hero we honor here today, Police Officer Joseph Swierczynski.”

Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey took the podium and added: “It doesn’t matter how long ago the even took place. When a member of our family loses his life in the performance of duty, we never, ever forget. Not only don’t we forget them, we don’t forget their family as well.”

This “Hero Plaque” program honoring fallen cops and fireman is thanks to lawyer James J. “Jimmy” Binns, who you might remember as Rocky Balboa’s lawyer in Rocky V, as well as the Pennsylvania Boxing Commissioner in Rocky Balboa. Joseph T.’s plaque is the 47th in Jimmy’s program.

“A great pleasure to welcome the Swierczynski family here,” Binns told the crowd. “This is now hallowed ground. This will never be disturbed. It will never be defaced or displaced.”

As Pennsylvania state rep Babette Josephs read the proclamation, she mistook Joseph T.’s great-grandson Steve Swierczynski for a member of the Philly PD. “The best police department in the universe,” Josephs said.

Steve, who was actually a lieutenant with the Cherry Hill, New Jersey police department, smiled politely, even as people murmured, “Cherry Hill.”

Commissioner Ramsey joked: “We’ll take him.”

Then Joseph T.’s great-grandson — and my cousin — Steven Swierczynski was invited to address the crowd.

“Joseph Swierczynski was my great-grandfather,” he said. “As I stand here before you I’m humbled. I’ve never been more proud to be a police officer. The show of support by my fellow police officers, who did not know my great grandfather, is heartwarming. It doesn’t matter if you knew him or not, he was one of us. A policeman. I’d like to thank my fellow officers in the Cherry Hill police department. I’d like to thank my wife. It’s not easy to be the wife, the daughter, or the son of a policeman. It might be even tougher to be mine.”

At this point Steve shot a a faux-stern look into the crowd, presumably at his kids, then smiled.

Soon a bugler played “Near My God to Thee” as Steve lifted the police flag, revealing the plaque.

Directly above the memorial was a sign for Lorzeno’s Pizza advertising:

Philly Cheese Steak

Chicken Cheese Steak

Hot Italian Sausage

Italian Hoagie

Cheese Burger

Fries * Wings

Order Inside

DJ Bob Pantano told the crowd, somewhat ominously: “See you next time.”

Wednesday December 12, 2018

I am jet-lagged and painfully hungover when I drag myself out of my AirBNB bed this morning. I pull on jeans and a button-down shirt and stagger down 2nd Street, toward Queen.

St. Stanislaus is no more. The church is still standing, but the parish has merged with St. Philip Neri at 218 Queen Street — “U.S. Birthplace of the Forty Hours Devotion,” in case that means something to you.

It probably should mean something to me. I was raised Catholic. I was an altar boy. I spent my high school and college years playing the church organ, at least two masses every Sunday. By the time I reached by early 20s, however, I realized I didn’t believe. Not in the way I was supposed to, anyway.

And after losing my daughter just six weeks before, you might say that God and I had some… issues.

So my hungover self is setting out for 7:30 a.m. mass as a historian, not a recovering Catholic searching for some kind of spiritual balm.

My early morning visit is not promising at first. Outside fences are padlocked shut. I walk around the left side of the building, to see if maybe another entrance is open. And there is! But not an entrance to the main church. This door leads to a small chapel nestled along the side of the building.

I presume the main church must be sealed off for repairs — or has been allowed to decay. Maybe weekday attendance is way down, and they’ve downsized to the chapel. The chapel is a very small room, humble electric organ in the back, modest altar up front. Pillars block the view from certain places in the pews, including where I sit—off to the right, toward the back. I am here as a neutral observer.

Three old guys already seated say, “Welcome,” as I step out of the cold.

Their voices: Welcome. Their eyes: Who the hell are you?

I sit down, forget to genuflect. It’s been a while.

A lone woman enters, followed by two more, all in their 60s. Three church ladies, directly out of central casting. They discuss who will do which reading. Soon the priest enters, spots me, says, “Welcome.”

His voice: Welcome. His surprised eyes: Who the hell are you?

The priest changes from his outside jacket and gets the party started. I try to mumble along, but they’ve changed some lines here and there. Probably to catch people like me who haven’t attended mass in a couple of decades.

The priest sings an alleluia, expecting us to respond in kind. One of the older gents really goes wild with it. The priest jokes, “Well, we won’t try that again.” (This priest, it turns out, is filling in for the regular pastor, who was ill.)

During the offerings of thanks and the mention of the recent dead… well, that blindsides me. I tear up. Jesus. (Literally.) I try to pull myself together. Can’t be losing it in front of the Church Ladies. During the offering of peace there are no handshakes, just eye contact and polite greetings. And soon mass is over. I remember liking weekday masses when I was an altar boy; they were master classes in concision.

I linger for a moment, wondering if there was a way for me to sneak into the main church. Decide against it — besides, this wasn’t where Joseph T.’s requiem mass had been held, anyway. I’d have to break into a completely different church a few blocks away.

As I follow the older gents outside, I wonder what impulse had brought me here this morning. Was it merely history? Or was I looking for something else?

These days I was operating on pure instinct. Maybe this was dormant instinct — memories of Polish funerals past. What I was “supposed” to do. We didn’t hold a funeral mass for Evie. Like her parents, she wasn’t a believer. A mass would have been hypocrisy.

I’d read that during the 1918 outbreak, some funeral masses were held on the front stairs of the church to avoid spreading the virus. I wondered if that is what happened with my great-grandmother Maryanna and my Great Aunt Marta. I also wondered how their coffins were transported all the way to Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon (where Joseph T. was also buried) more than eleven miles away? Was there a horse and carriage? How did the grieving family travel?

So many things I don’t know. Will possibly never know.

I retrieve the rental car (a white Chevy Impala, just like local cops drive), happy to find it on Front Street without a ticket.

I head north on Columbus Boulevard. I am old enough to think of this street as Delaware Avenue, even though it hasn’t been called that in a few decades. I make a left onto the usual I-95 ramp to Northeast Philly when… whoa. Since I was last in town a huge monstrosity of a condo has been slapped up, dwarfing the historic Water Street block (with its equally historic steps). I also soon discover they are still working on I-95, this time tearing down the southbound lanes. They will be building, and rebuilding, this highway forever.

The drive down Cottman Avenue in the Great Northeast is predictably depressing — family memories flood my mind. This is our old neighborhood, where the kids spent their childhoods. I haven’t been here since we moved. My hungover self tells me I need carbs and caffeine, so I buy three soft pretzels and a Brisk iced tea. Then I continue on to the storage facility in Elkins Park, just outside city limits.

I’m back here in Philly to do research, but I’m also here to bring back some of the Daughter’s things. I pull up, key in, ride a freight elevator upstairs, snap open a padlock. It is attached to the keychain with some of the Daughter’s ashes in it. Part of her is with me for this journey.

I pull up the segmented metal door and am immediately greeted by the huge stuffed animals we’d bought for the kids three Christmases ago: a kangaroo (for Evie) and a camel (for Parker). They’re guarding all of the things we left behind when we moved to Los Angeles.

They give me a disapproving look: Where the fuck have you been? Why did you leave us here?

This is much a sadder experience than I anticipated. Evie is everywhere. These were the pieces of our lives we left behind for the moment—photos, art, toys, doll clothes, holiday decorations, memory books, videotapes. In short: everything that wasn’t a huge priority while moving two and a half years ago. But these things mean everything now.

Fuck me. How am I supposed to do this?

I pull out some things for home (pieces of Evie-made art, videotapes from pretty much every Christmas, scrapbooks) as well as a box of Philly history/crime books. The next day I would mail the latter home, while I transported Evie’s stuff with me in my backpack and suitcase — they were too precious to risk losing.

After enduring as many memories as I could, I sat there in that storage locker and cried.

No… I wept.

Here’s the weird thing about grief. At some point, the tears stop. The body simply can’t do it anymore. Not right now, anyway. So you gather yourself, you pull down the storage locker door, you say goodbye to the kangaroo and the camel, you put one foot in front of the other and propel yourself forward, operating on sheer instinct.

Back at 107 Christian I shower, change, and set out to walk Joseph T.’s beat again, this time in the daylight hours. My midday goal is to have a slice of pizza where he was shot and killed.

I walk down Catherine this time, aiming to end up at the intersection of 9th and Catherine where Joseph T. stopped the holdup of the black man. I surveyed and photographed the corners.

Near the northwest corner is Ralph’s, a classic Italian eatery that’s been around since 1900. On the southeast corner: the former location of Palumbo’s, also around at the time. Maybe the “colored man” (as the papers referred to him) made the mistake of walking past a neighborhood under the control of Zanghi and his little gang, and they shook him down. Maybe he resisted the shakedown.

In the words of my Grandpop Lou: “The Italians fought the Poles. The Poles fought the Irish. The Irish fought the Italians. Everybody fought the blacks.”

I use my phone to shoot a video of the block-long walk to the saloon, now a pizza joint. Then I step inside.

It’s a South Philly pizza joint.

I order a slice and a small Diet Coke, then perch at the counter facing Ninth Street. There is a side door that was probably the same door from 100 years ago — the one where (allegedly) the witnesses to Joseph T.’s murder scurried through on their way out of the saloon.

I sit there and try to puzzle out what is original, what has been added. I try to magically conjure the saloon from a century ago.

There is another couple, older, eating lunch at one of the tables and eyeballing me cautiously. I ask the counter guy for permission to take some photos. The counter guy says sure. He’s also eyeballing me cautiously.

So much has changed. I can’t even tell where the bar may have been. I wonder if any vintage photos exist, and if so, who might own them. I wonder what’s hidden above that drop ceiling. I feel like I’m on the beach scrambling to scoop up shell fragments before the tide carries them away forever.

I finish my slice (which is very good, by the way) and settle my modest tab. Outside, I brush some debris from the Joseph T.’s hero plaque. It has been more than a decade since its placement. I wonder if anyone stops to look down at it as they’re enjoying their own slices, baffled by that last name.

As 1919 rolled on, my widower great-grandfather remarried. So did Joseph T.’s widow.

This may seem a bit sudden to modern sensibilities. But my great-grandfather had a house full of children (including my grandfather, who would turn 2 that year) and a full-time job at the sugar factory. Practically speaking, he needed the help. Joseph T’s widow had the opposite problem: she had two young boys and needed the financial support. Grieving never stops, but life has a funny way of moving on whether you like it or not. You have to figure things out best you can.

Meanwhile, the City of Philadelphia prepared its case against Anthony Zanghi, who would celebrate his 20th birthday in Moyamensing Prison. And forces allied with Zanghi would prepare his defense.

Including a somewhat unusual choice for a defense attorney…

As always, a great read. And my heart still hurts for y’all, Duane.

Thank you for sharing this. Can’t wait to read what is coming next.

A ft

Having also wept for what is lost in a storage container, I want to tell you to not go alone next time!