The Hungover Detective

Man Full of Trouble (Chapter Two): Death on the Half Shell; Hold My Beer; Little Clues; Turkey and Stuffing and Cranberry; The Motive

This is the second chapter of my pulp non-fiction gangster memoir, Man Full of Trouble, detailing the rise and fall of the gangster who killed a family member 100 years ago. I’ll be sharing chapters each week through March 2025. (You’ll find chapter one here.) Comments and questions are welcome; huge thanks to the paying subscribers funding this book.

Trigger warning, no spoilers: this chapter is heavy.

Tuesday, December 11, 2018 (continued)

I walk back down Christian Street. Half a block away from my rented room, I have the sudden impulse to hang a right on Second Street and wander three blocks south to Snockey’s. The legendary seafood joint closed a few years back, right before we moved to L.A. But a quiet voice urged me to take a look anyway.

Standing on the other side of Second Street, I tried to reconcile my memory with the place I was now seeing. The humble white-tile restaurant has been reborn as “Snockey’s Landing”—a short stack of condos. If you stand still long enough, you’ll be turned into a condominium, too. But in this case, the building was sort of returning to its original use as a hotel. When my grandparents were growing up in this neighborhood, it was probably a flophouse.

The sight of this building takes me back in a huge way.

Spring 2014—I was writing Revolver and piecing together my own family history. I’d recently discovered the addresses of my grandfathers’s childhood homes, and was stunned to realize they grew up just a few blocks from each other. Like, drunken crawling distance. (And yet, my parents would meet elsewhere in the city, many decades later.) Grandpop Walter was nine years older than my Grandpop Lou, but surely they must have crossed paths. Maybe they even bumped into each other at Snockey’s at some point.

So on Sunday, April 14, 2014, I decided to explore the neighborhood, and asked The Daughter to come along with me.

She agreed because I promised clams for lunch. (Evie was up for any adventure, so long as it involved food by journey’s end.)

And not just any old clams, but clams from Snockey’s— founded by Frank Snock, a 20-year-old Polish immigrant who borrowed $50 to take over a former restaurant at 142 South Street, along the northern border of Southwark. Opening day was May 3, 1912, the same day Frank’s wife gave birth to a daughter. “She worked for a bit, went into labor, went upstairs, a midwife came in, and she had the baby,” grandson Skip Snock told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2014. “Two days later, she was back in the kitchen.”

Grandpop Lou was a lifelong fan of Snockey’s. When he was a boy, they were located at Second and Fitzwater, five blocks away from his home at 126 Christian. Grandpop Lou loved to tell me stories about how cheap the oysters were, how many he’d carry back home. Old people really enjoy talking about food. I don’t mind. I prefer cool old stories about food than Instagram photos of food.

Anyway, I figured that The Daughter would enjoy a trip to her great-grandfather’s favorite oyster and crab (and clam) house after forcing her to pose in front of not one, but two ancestral family homes: the one at 126 Christian Street (maternal, the Wojciechowskis), and 106 Kenilworth (paternal, the Swierczynskis).

In the first photograph, on Christian Street, Evie played it straight as she leaned against the concrete stoop, subtle smile on her face, looking wiser than her eleven years. Just chilling, she’d say.

But in the Kenilworth Street photo, she’s full-on goofing for the camera. doing an unconscious imitation of Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

At the time, I didn’t realize how special this day would be.

How prophetic.

Snockey’s had the aromas of an old-school seafood house, like you were inhaling the ghosts of countless meals past. Evie ordered linguini and clams. I took photos of her prying open a littleneck. She loved posing with her food. She loved restaurants.

And I would give anything to be sitting across the table from The Daughter right now, telling her about this book instead of actually writing it.

I have to apologize, because I am about to punch you in the face.

This is my standard warning when I meet someone who doesn’t know. And it’s quite possible you don’t.

October 30, 2018—a Tuesday evening. My daughter is dying.

Her mother, brother and I are by her side. We take turns holding her hands, telling her how much we love her. My God how we love her. We are at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles on Sunset Boulevard. None of this feels real. How could it be real? The resident pediatric doctor assures us that it won’t take long once he removes the breathing tube and the various machines and drugs that are keeping her alive. She will slip away in a matter of minutes, he says, painlessly.

But Evie must hear that and think hold my beer, because it takes more than two hours for her heart to stop beating. She’s always done things her own way.

Time of death: 6:35 p.m.

Evie Swierczynski will always be 15 years old.

She had been diagnosed with acute myeloid lukemia exactly five months before. Her particular genetic mutation was rare, which meant that chemotherapy alone wouldn’t work. She needed a bone marrow transplant—which she received on September 13. It worked. Forty days later, she was cancer free. But the transplant process had ravaged her body, and her organs began to fail. I spent the night of October 29 listening to the PICU team discuss, in hushed tones, all of the things that were failing. By morning I knew this was going to be her last day. No one told me, but I knew. I splashed water on my face in the visitor bathroom and heard an oddly-calm voice tell me: Strap in. This is going to be the worst day of your life.

After Evie dies, we somehow pack up all of the things in her room—and there is lot, since we’ve been practically living here (and in other CHLA rooms) for the past five months.

I drive the three of us home, crawling along rush hour traffic on Los Feliz Boulevard. How am I able to drive? I drive because I have to. Otherwise, how will we get home? It’s as simple as that. But this is all wrong. There should be four of us. It’s always been the four of us.

Back at our apartment our son, 16, is hungry. He’s been at the hospital all day with us and hasn’t eaten much. This is a Tuesday night, so there is a food truck in the driveway to our complex. We walk our dog and buy our son dinner.

We go to bed but can’t sleep, because we’re waiting for this particularly realistic nightmare to end, and maybe we’ll wake up and everything will be okay again.

But that requires sleep.

And there will be no sleep.

Grief is not what you expect. The movies depict it as a singular state of being: wearing black and being somber and detached from everyday life. But in truth, it is more like standing on the shore and being pounded by waves. Sometimes the wave will pull away and you’ll think: okay, this isn’t completely horrible. I can still function. I’m still standing, and maybe I’ll be able to… then BAM... another wave strikes you, bigger and more powerful that you ever imagined, to the point where you don’t even know you’ve been knocked over, or if your feet will ever touch the shore again. And then you do.

At the time of Evie’s passing I have three different novels underway. The idea of continuing with any of them feels absurd. Someone else started writing those—not me. For a couple of weeks, I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to write again.

The first thing I’m able to write is my daughter’s obituary.

We decide to have a “celebration” instead of a traditional funeral. The guests: Evie’s friends and classmates, as well as our local grown-up friends. Part of the celebration would be a slideshow of Evie’s life. I scroll through iPhoto and drag photos to a folder I’ve set up. I ping-pong between laughing and weeping. I’m a fucking mess. One photo from April 2014 jumps out at me.

The Daughter, in front of that brick rowhome on Kenilworth Street.

I am desperate to be back in that moment, desperate to push my consciousness back in time to tell my younger self to appreciate this utterly fucking special sliver of time. But if time travel is a thing, I haven’t learned how to do it.

I close iPhoto. I can only do this in shifts. Trying to do it all at once is way too much.

But for the rest of the day, something about that Kenilworth Street photo nags at me. Something about that house, in the past. A piece of family history I had uncovered but am now forgetting. I reactivate my Ancestry.com account and start looking through the tree I started in spring 2014. I find it fairly quickly. Four years ago, it struck me as tragic. Now, it flat-out stuns me.

My great-grandfather Anthony Swierczynski lost his second child, a daughter named Marta, who was 15 years old.

Exactly one hundred years ago.

Marta, along with her mother, my great-grandmother Maryanna, perished in the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918.

The Philly epidemic broke out in late September 1919, killing most of its victims during the month of October. Which means that my daughter and great aunt were the same age when they died, one hundred years apart:

Marta Swierczynski: 1903 – 1918

Evie Swierczynski: 2003 - 2018

Marta, like Evie, will always be 15.

But there’s more, says a voice in my brain.

This voice leads me back to the research notes for a book I had intended to write after Revolver. Later chapters of that book pointed to the Prohibition era—hints of what was to come. This is not unusual. I like to leave myself little clues about where I might want to travel next.

That historical crime novel would have been called Man Full of Trouble, and the fictional plot would have included the real-life murder of patrolman Joseph T. Swierczynski, shot and killed in the line of duty on March 20, 1919. But now I consider the murder in a slightly larger context. Joseph T. was murdered just six months after my great-grandmother Maryanna and Great Aunt Marta died. For the Swierczynski family, new immigrants to America, it had been an unrelenting season of grief. How did I not know about this? Something so epic and tragic in my family… surely, this would have been discussed for decades? But these were stories I had to discover for myself.

In short, Fall 1918 through Spring 1919 was not a good time to be a Swierczynski.

Fall 2018 heading into 2019 isn’t that great, either.

So I decide to dive back into the research—the murder of Joseph T., as well as what happened to my great grandmother and great aunt. I am desperate to know more, even if it is just a temporary escape from my own grief. My wife doesn’t exactly understand what I’m doing. I’m not sure I do, either. But it’s the only thing that makes sense right now. Work has always saved me, ever since I was a kid. Whenever I felt threatened or overwhelmed or sad, I retreated into a book. And eventually, I took similar comfort in creating my own stories. I hated the world I was living in, so I escaped into others. I am doing the same thing now.

All of my research files are in storage back in Philadelphia, so I decide to travel back home to dig them out. And while I’m there, walk around the actual crime scene.

My wife says she understands. (Later she admitted she really didn’t, and was worried about me.) I don’t tell any relatives back in Philly about my plans. I didn’t want this brief trip to turn into something else. If I stayed downtown, I wouldn’t run into anybody unless I wanted to.

Two days before Thanksgiving, I book a flight and an AirBNB apartment on Christian Street, exactly seven and a half blocks away from where Joseph T. was killed.

Thanksgiving 2018 feels okay at first. We watch movies. I put on Netflix and watch the new Coen Brothers—The Ballad of Buster Scruggs only to discover that the film is a multi-part study of grief, death and loss. As I’ll soon discover, an absurd number of movies are a multi-part study of grief, death and loss. Maybe this is the only thing human beings really tell stories about.

I mix a Bloody Mary, because that’s what I do on holidays and the occasional Sunday. Say what you will about my crime novels, but I am fucking Amadeus when it comes to the Bloody Mary. Celery salt is your friend; black olive and pickle garnishes are key.

In years past, whenever I’d take a test sip of my freshly-mixed Bloody Mary, I’d pause to appreciate my genius and announce to the room, “Damn, I’m good.” It’s a joke. I never claim to be good at anything. The Fam would roll their eyes. The Daughter would roll hers the hardest. Nobody else in the family drinks Bloodies—the kids are too young, and my wife hates tomato juice. I did make The Daughter a virgin Bloody once, and she claimed to enjoy it. She did not, however, admit that it was damn good.

My wife prepares dinner, sets the table.

But by the time the turkey and stuffing and cranberry sauce and green beans are set down in front of us, her empty seat is too much. My wife feels like every bite will choke her. I can’t breathe. After forcing a few bites food, I lay down and focus on filling my lungs with air, one gulp at a time. My heart races so fast I think I am on the verge of a heart attack. It is too soon, too soon.

What the fuck were we thinking?

It’s a not even a month since she passed away. We’re keeping her room untouched, and the dreading the day we have to pack it up and move somewhere else. We’re in a relatively pricey apartment in downtown Burbank. Leases don’t run forever.

Evie’s phone is still active. We can’t bring ourselves to disable service.

The morning of December 8 I am hungover because I drank too many old-fashioneds the night before. Despite this, I wake up determined to pin down the exact dates Maryanna and Marta Swierczynski died.

I ask Evie for help. I don’t want to make a habit of this—the last thing I want to do is bother her, even in the afterlife. But in this case, I need her guidance. Help me figure out how to find the death certificates for your great-great grandmom Maryann and your great-great Aunt Marta.

Just a few minutes later, in one of those blind moments of pure internet luck, I stumble across a no-frills PDF list of death records in Pennsylvania for the year 1918. I scroll through until I find my great-grandmother. Her surname is mispelled:

Maryanna Swierczinskie; --155299; Phila; Sept. 30.

A full life, including a tough journey halfway around the world, reduced to a single typed line.

But there is no sign of her daughter Marta.

There is a “Martha Swiertz” who died on May 12, 1918 in Mt. Carmel, Pennsylvania (up near Bloomsburg). But that can’t be her. Unless Great Aunt Marta died earlier in the year, in another part of the state.

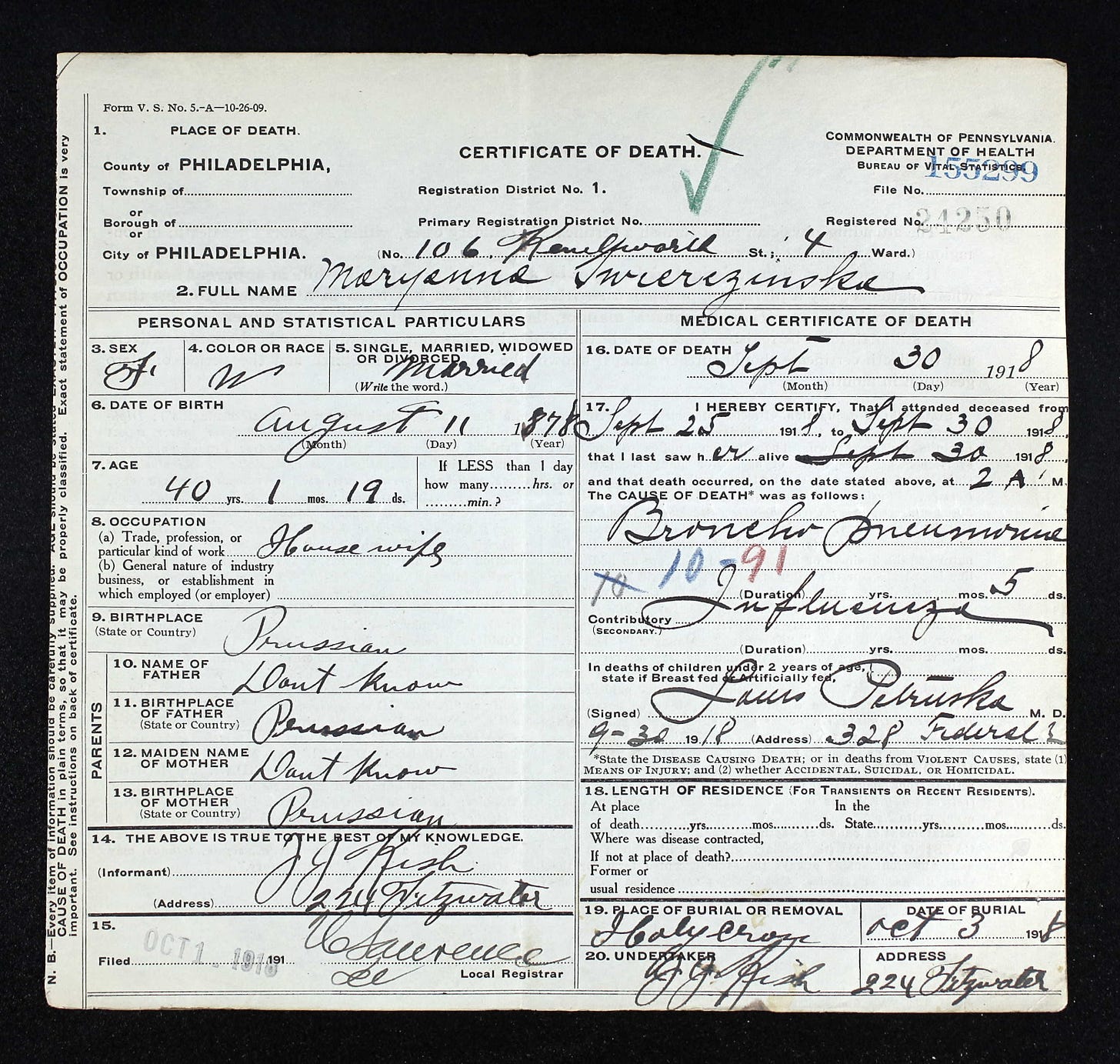

I recheck my great-grandmother’s listing to see what else I can use. There’s that number: 155299. Using it I am able to slowly track down her death certificate using the browsing feature at Ancestry.com. After about forty minutes, I find a scan of her actual death certificate.

Maryanna Swierczynski died at 2 a.m. on September 30 from broncial pneumonia due to influenza. She had been sick for five days. She was only 40 years old.

It made sense that Marta would have died around the same time. Perhaps she was caring for her ailing mother, then became ill herself? I start to browse forward in time, then move backwards. The names of the dead roll by. So many names. None of the them are my Great Aunt.

I go back back to the original no-frills PDF. Is it possible that Marta’s surname has also been mangled, but in a different way?

Yes. It is entirely possible:

Swerczinska, Martha; --151842; Phila; Oct. 5.

And using that number, I am able to find a scan of her death certificate, too.

My Great Aunt Marta died October 5, just five days after her mother passed—and a mere two days after her mother’s funeral. It is doubtful that she was able to attend. I have no way of knowing who was healthy enough to be graveside. Three days later, Marta was laid to rest next to her mother in the same Catholic cemetery on the outskirts of the city.

I can’t believe something so tragic as losing a 15-year-old daughter can be forgotten within a generation or two. Nobody ever talked about it in my family. I didn’t know about Marta until I went looking at our family tree. How can this be? Why wasn’t the story of this impossibly sad time passed down?

One hundred years from now, will our descendants know nothing of Evie?

This is why I’ve flown back to Philly.

When we die, it’s possible that linear time ceases to be a thing. It’s also possible that we realize we’re individual aspects of one whole. And it’s possible that place/distance between places have no meaning, either.

If this is the case, this entire book I’m writing is useless, since it’s an attempt to lay down a timeline and tell stories about individual people lost to time, entirely centered on a specific place. The dead have no use for this book. It’s for the living, struggling to solve mysteries that are plainly obvious to the dead.

Maybe I’m writing a mystery where The Daughter already knows all of the answers.

Eloquent description of grief. God bless Evie