The Family Ghosts

Man Full of Trouble (Chapter Three): Enter Musky; Drinks at Lucky's; Thinking About Her Chest; The Smile in the Mirror; A Canister of Gasoline

This is the third chapter of my pulp non-fiction gangster memoir, Man Full of Trouble, detailing the rise and fall of the criminal who killed a family member 100 years ago. I’ll be sharing chapters through March 2025. (Here is Chapter One and Chapter Two.) Comments and questions are welcome; huge thanks to the paying subscribers funding this book.

Tuesday, April 18, 1916

This is not the Heist of the Century.

This is just a nine-year-old kid taking a lunchtime walk to a bank in sleepy and dry Haddon Heights, New Jersey. He’s a good kid with a pocket full of cash to be deposited into his family’s Christmas club account.

Three tough guys approach the kid near Atlantic and Garden. The newspapers will describe them as “Italian youths,” and they want this kid’s money. The nine-year-old doesn’t want to give it to them. And why would he? This money belongs to his family.

A fight breaks out. The nine-year-old is hopelessly outnumbered, outmatched.

But…

At the same moment, a Haddon Heights patrolman named Sproule happens to be home eating lunch. His son is gawking out a window when he starts to freak out. Dad! There are boys! Fighting out back! At the moment, Sproule is off-duty. No weapons, no uniform coat.

But he’s still a cop. Sproule leaves his meal and darts outside.

And yeah, his son is right. Three teenaged hoods are beating up some poor nine-year-old. When they see Sproule, they bolt. Sproule pumps his legs and manages to put hands one of them. But his two companions escape.

Oh… now it’s on. Because Sproule really wants those other two hoods.

Sproule flags down a milk truck driver named Ralph Buckley. Here. Watch this kid. I’m going after the others! Buckley agrees.

Sproule takes off.

But the other two Italian youths? Oh they’re gone gone.

That doesn’t mean Sproule gives up. He flags down another driver — a dude who works for Bell Telephone. They speed down White Horse Pike, looking for the other two bandits. No luck. Two miles of frenzied searching, and nothing.

Where are these fucking kids?

Spoule decides to go back home and start from the beginning. These punks have to be around here somewhere.

Sproule and the Bell Telephone guy go searching the neighborhood and… wait. There. In that field. Near Ashland. The other two punks. They duck down behind some trees, but Sproule knows they’re there. The two adults split up and move in from opposite sides. The punks have no escape. Sproule grabs one; Bell Telephone guy grabs the other. You’re coming with us.

At Haddon Heights police headquarters, the punks fess up their names:

Bernard Cordilo, 708 Percy Street, Philadelphia

Peter Maurio, 723 South Tenth Street, Philadelphia

Anthony Zanghi, 838 Montrose Street, Philadelphia

Three Italian youths, all from South Philly.

But pay close attention to that third name: Anthony Zanghi. He’s only sixteen.

Later, they’ll call him “Musky.”

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

More than a hundred years later and 10 miles away, I could use a drink.

I consider For Pete’s Sake at Front and Christian. But as I walk up Second away from Snockey’s Landing, a bright sign catches my eye: Lucky’s Last Chance.

Those last two words jump out at me, sure. What could be more noir than last chances? But the bar is also across the street from the site of the former police station where Joseph T. Swierczynski worked. Something about the place says, hey, give me a try. And these days, I’m running on pure instinct.

I look up Lucky’s on my phone. The menu and tap list seem promising. Then again, any bar right now seems promising.

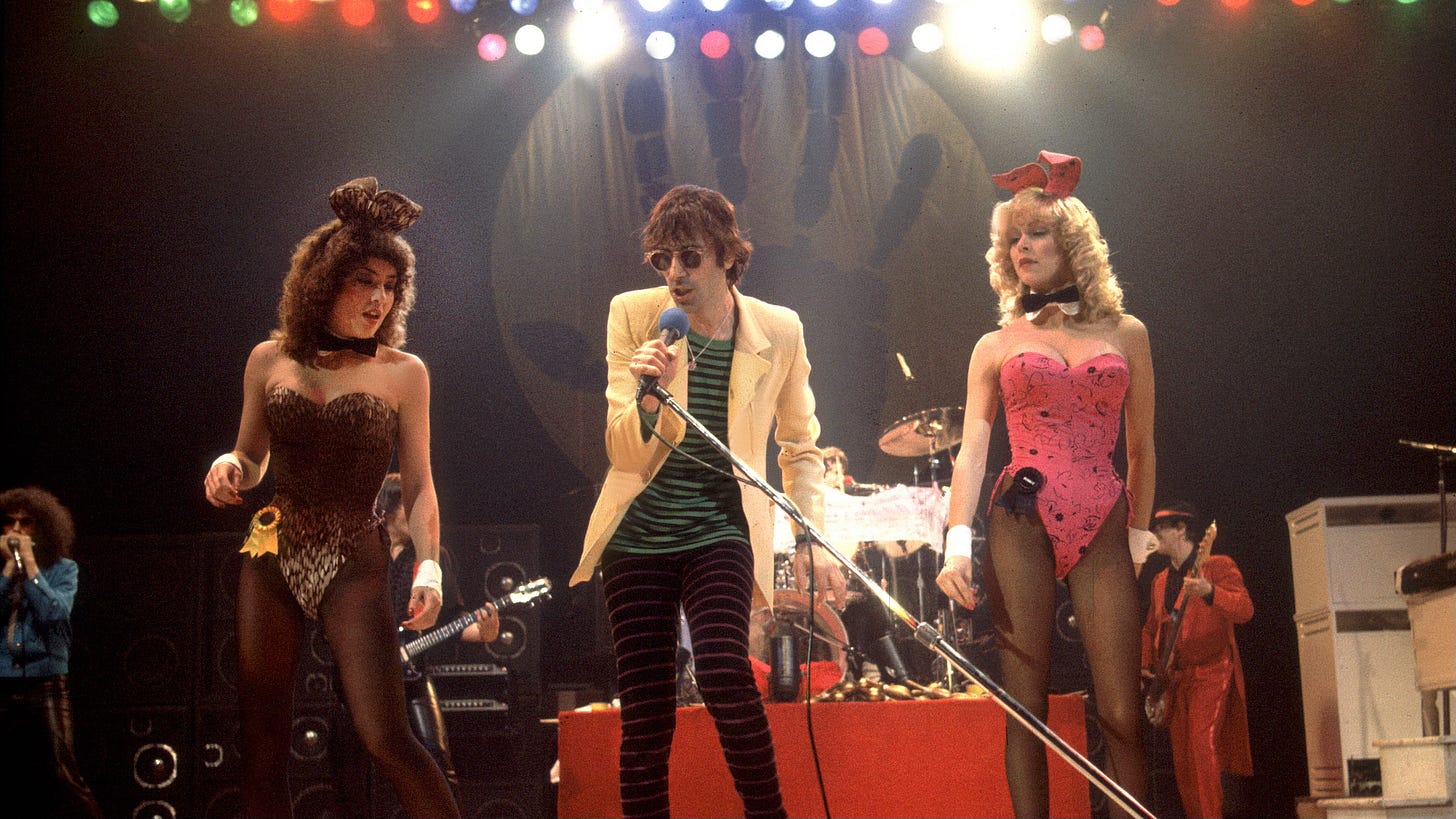

Bars have always been a safe haven. I grew up in Philly bars. This may sound weird, considering I’m a Catholic school honors student. But around 1981, my dad decided he needed a keyboard player for his bar band, so I was pressed into service. He taught me rudimentary chord changes. I learned a lot of Beatles, Stones, Doors. I listened to 45s and I did my best to imitate the keyboard riffs I heard.

By early 1982 I was 10 years old playing classic rock covers in dive bars in Kensington, not far from where the fictional Rocky Balboa lived and trained.

The bar was called Dimitri’s, right near the fabled intersection of Kensington and Allegheny, a.k.a. “K&A.”

The best part about playing dive bars? Watching the adults and how they behaved. Sometimes the drunks would give me a few quarters, which I would pump into Donkey Kong machines during set breaks.

I also loved that I could ask for free Cokes and bags of Wise potato chips whenever I wanted.

I enjoyed playing the keyboard riff to The J. Geils Bands’ “Centerfold.” My keyboard could almost imitate the blend of synth horns and a bleating organ. Being 10 years old, I didn’t understand all of the lyrics to “Centerfold.” But my father didn’t exactly help. He liked to fuck with the cheat sheet lyrics. Where the original line might have gone:

Slipping notes, under the desk

I was thinking about her dress

My father would write:

Slipping notes, under the desk

I was thinking about her chest

I was shy. I turned away, before she caught my eye.

Back at 107 Christian I put on real pants (meaning a pair of jeans; I’d traveled in gym pants) and step back out into the cold night air. Down Christian, right on Second, and barely a half block to Lucky’s. I didn’t know it at the time, but Lucky’s would become my home-away-from-home on this trip. Sorry, Pete’s.

Looking up Second, a few street and shop lights illuminate doorways here and there. The rest fades into a wintry black oblivion, like a first-person video game, where only the necessary elements are illuminated as you explore.

Lucky’s turns out to be a cozy Philly-style neighborhood bar, the kind you don’t see much in L.A. There are only a half-dozen customers inside on this Tuesday night. I pull myself onto a stool and order a Philly Pale Ale.

“What can I get you?”

The bartender’s name is Shannon.

“Uh… a Philly Pale Ale?”

“You got it.”

I make some small talk with Shannon, mostly because I haven’t had a real conversation with another human being all day. She’s friendly, but guarded. After all, I am a stranger. I’ve always felt like a stranger in my hometown.

Lucky’s opened as the Kennett Cafe back in 1924, two years before my maternal Grandpa Lou was born. I’m fairly certain he could have seen the cafe entrance from his own front door at 120 Christian Street. Maybe the Kennett was his first-ever image of a bar — even though this was Prohibition, and any alcoholic beverages would have been served up on the sly. I wish he were here so I could ask him.

On the opposite end of side of the bar, some random dudebro begins to complain (loudly) about L.A. Seems the City of Angels doesn’t impress him. Like, at all. I have no idea what prompted this opinion, but I can’t help but feel the universe was trying to tell me something.

I don’t tell him I’m currently living in Burbank.

I don’t say a thing.

After draining my Pale Ale, I ask for a Delco Lager and a “naked dog” with sauerkraut and tater tots. Comfort food. And you know what? That shit works. For a few minutes, I felt comforted.

Kennett Cafe was around for decades and has a semi-notorious history. In June 1963, police broke up a local numbers racket near Second and Catharine, and four gangsters went scurrying out, desperate for hiding places. One of them, “Sonny” Masculli, Jr., darted into the Kennett and ordered a beer. That didn’t fool the the IRS men, who arrested him mid-sip.

I truly hope Sonny offered to buy them a round before they squeezed the cuffs around his wrists. That would have been gangster.

Decades later, the bar became a notable restaurant featuring Kale salads and Prohibition-style cocktails (the Inquirer’s Craig LaBan said this “long-troubled Queen Village bar finally landed a worthy tenant”) before Lucky’s bought the place. Later I’d find a Prohibition-era classified ad for the Kennett Cafe, looking for Polish cooks.

I buy two cans of Narragansett “Fresh Catch” to go and I’m instantly blasted with memories of a family trip to Maine a few years back. Evie and I were the only ones brave enough to crack into full lobsters, tomalley and all. Back then, I washed everything down with a Narragansett tall boy.

I would give anything to slide back in time to that trip.

Shannon the Bartender tells me one of the Fresh Catches are on the house. Which is sweet, and seals the deal. Lucky’s is my new home. It is not difficult to buy my barroom loyalty.

I leave with my cans of Narragansett in a plastic bag and wander north on Second, very wide awake. It’s still light back home in California. If I retreat to 107 Christian now, I’ll end up drinking these cans of beer and staring at the walls. There will be plenty of time for wall-staring later.

A few blocks north, I turn right onto Kenilworth Street. Might as well meet the ghosts of the Swierczynski family. After all, this is partly why I’m here.

Halfway down the block is 120 Kenilworth, where police officer Joseph T. Swierczynski lived with his wife and very young sons.

I stop and look up at the home. Cold wind off the Delaware River blasts against my body, trying to find a way into my bones. I pull out my phone, take a few photos.

Hello, Joseph T.

Did any Swierczynski think a descendant would be standing here, a century into the future, trying to puzzle out their daily life?

If so, none of the family ghosts say a word.

What I know about Joseph T. comes through three main sources: newspaper articles, my family tree, and my distant cousin Steven, who is Joseph T’s great-grandson.

I first met Steven Swierczynski at the Saloon, a legendary South Philly restaurant, back in the spring of 2014. I chose this location for a number of reasons. One: the Saloon was a notorious Philly mob hangout. (So yeah, duh.) Also: this used to be part of Joseph T.’s beat. And finally: it’s a short distance away from where Joseph T. was shot and killed. I figure this is Ground Zero of our family’s history.

The weirdest thing about meeting Steven was how much we resembled each other.

Not in an obvious, holy shit you must be twins! kind of way. But if you were to look at us hanging out at a dinner table, you’d think: yeah, they’re totally related.

Steven is two inches taller. But when he smiles… goddamn if it isn’t the same smile I see in the mirror. He also has my deep set eyes. Steve told me I look a lot like his younger brother.

Until that day, we’d never met.

How does this happen to families? One hundred years ago, an entire generation of Swierczynskis grew up on the same narrow street, close as can be, gathering for holidays and birthdays and awful days. All of them, spent together. Skip a century and the same family is scattered across the city and New Jersey and many points beyond, unaware of each others’ existence.

After lunch Steven and I walked over to Kenilworth Street, where both of our great-grandfathers raised their families. We stopped at 120.

The same rowhome I was staring at now.

We walked over to Ninth and Christian, where Joseph T. Swierczynski was shot and killed by Anthony Zanghi. A plaque honoring him was planted in the sidewalk, just to the right of the entrance to Lorenzo’s Pizza. One leg of a metal folding chair leg stabbed it in the upper middle. The plaque hadn’t been cleaned or cared for in a while.

Steve said the owner promised to always care for the plaque. Maybe she died, he said, staring glumly down at the sidewalk.

The same green-and-white tile entranceway from 1919 was still there. We reached down and pressed our fingertips to it. The tiles were cold.

They are always cold.

(Go there now. Feel the tiles for yourself.)

At the time, Steve suspected our great-grandfathers were brothers. But later, thanks to some vigorous family tree research, I discovered the truth: Joseph T. was the much-older cousin to my Grandpop Walter. My great-grandfather, and Joseph T’s father, were brothers, both born in Poland.

Later, in October 2014, I had lunch with Steve Swierczynski and his uncles Paul and Joe. Paul’s and Joe’s father, Joseph B., used to worked at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. He once carpooled with a laborer named Zanghi—possibly the son or nephew of Anthony “Musky” Zanghi, the man who killed their father. Joe also attended high school with a girl whose last name was Zanghi. (“I rode the bus with her!”)

Philly can be small that way.

The Swierczynski men, they told me, could repair anything. “I never saw a repairman ever growing up,” said Steven.

My father, too, could also fix anything. Almost.

Steven and his uncles told me they never heard much about Joseph T. growing up. Their grandmother, Joseph T.’s widow, never remarried. She lived until 1971, a year before I was born.

In Joseph T.’s time, you had to know someone to get a job on the police force. Joseph T’s uncle—or possibly his wife’s uncle, they said—was a ward leader. That’s probably how he got the job.

Joseph T. joined the Philadelphia Police Department in late April 1917. His salary: $2.50 a day. Being a cop then is not like being a cop today. For one, they’re weren’t referred to as “cops.” They were “bluecoats,” a reference to their distinctive uniforms. This is no police union. There are no forensic labs.

There are, however, ward leaders. Ward leaders are controlled by the Organization; the cops are controlled by the ward leaders. Joseph T. is attached to the Second and Christian streets station, which covers the Third Ward, a fairly narrow strip of land stretching from the Delaware River a mile and a half to Broad Street. Its northern boundary is Fitzwater; Christian on the south, two-tenths of a mile away.Below it is the Second Ward; above it, the Fourth and Fifth.

They’re all river wards, teeming with immigrants fresh off the nearby boats.

I walk seven doors down Kenilworth to 106, where my Grandpop Walter was born. I think about Evie posing in front of its blue front door only two and a half years ago.

I peer down the alley on the left but can’t see anything through the dark. If this is a video game, this part of the landscape hasn’t rendered itself. The Swierczynski Family occupied this property deep into the 1950s, and possibly the early 1960s.

My great-grandfather Anthony John Swierczynski was a laborer at Franklin Sugar. Every day he’d put in his hours at the plant and then return home to 106 Kenilworth Street, a ridiculously short commute. If the sugar factory were a university, my great-grandfather’s rowhome could have been considered on-campus housing.

Where is Franklin Sugar now? Gone, like a spoonful in a cup of hot tea.

Let’s say you’re driving south down I-95, just past the Ben Franklin Bridge, and are suddenly transported 100 years into the past. Within seconds you’d be crashing into six-story brick behemoth that was the Franklin Sugar Company.

There’s no trace of the plant left now. It was torn down in 1967, and I-95 runs through its former footprint. If there are any ghosts lingering at the old sugar plant, they spend most of the day dodging speeding cars.

It’s kind of a miracle 106 Kenilworth is still standing.

Like the half-assed private eye I am, I walk around the block and try to find a way to the back of the house through an alley. But no luck. If there’s some clever way to sneak into the backyard, it’s beyond me. And I’m a little too old and tipsy to go hopping over fences and risking a trespassing beef.

Instead, I walk back around to the front of 106 and stare up at the windows, trying to imagine what I might have seen if I were standing here a century ago.

Come on, family ghosts. Talk to me.

I’m begging you.

Take me back in time and tell me how this all makes sense.

Tuesday, February 1, 1916

Inside 848 Montrose Street, just around the corner from Ninth and Christian, a canister of gasoline near a stove explodes.

The blast rocks the entire structure and adjoining homes.

Inside the home is the Zanghi family. The blast is a shock, and the worst of the injuries fall upon the youngest: five-year-old John, and five-month-old Jacob.

Two days later, Jacob succumbs to his burn wounds, leaving behind his parents and siblings. One of them is older brother Anthony, sixteen years old.

Later, they’ll call him “Musky.”