Return to the Scene of the Crime

Man Full of Trouble (Chapter One): Memory Loss; Christian Street; A Lesbian Swedish Thing; Nearer the West; Death Pizza

This is the first chapter of my pulp non-fiction gangster memoir, Man Full of Trouble, detailing the rise and fall of the gangster who killed a family member 100 years ago. I’ll be sharing chapters each Tuesday through the end of March 2025. Comments and questions always welcome; heartfelt thanks to the paying subscribers who are funding this book.

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Nothing looks familiar.

It’s not the city. It’s me.

After two and a half years in California my brain has purged all of my internal Philadelphia maps (well, boys, looks like we won’t need these anymore!) and replaced them with the sprawling freeways and assorted connective tissue of greater Los Angeles. Maybe I don’t have enough internal memory to support both?

But that would be absurd. Philadelphia is my hometown. I spent my childhood and the vast majority of my adult life here. Not long ago I could have driven to and from the airport on autopilot, and I have—picking up family, dropping off friends.

At this moment, however, I have no earthly idea where the fuck I am or how to get out of this parking lot. I am baffled by traffic signs and cling to every syllable of my phone’s GPS. Why can’t I remember these streets? Where is I-95? Why is it so dark? What has happened to my brain?

After a ridiculous amount of time circling in the dark, I steer my rental car onto the ramp that will take me to I-95 North. Ah, 95, the industrial mother road, which hugs the curves of the mighty Delaware River! I remember 95! All must not be lost. It is still early evening and traffic isn’t so bad. My brain thinks it should be 2:30 in the afternoon and sunny. Instead, it’s freezing and pitch black and I’m hastily downloading place-memory files I didn’t know I’d deleted.

Gliding over the Girard Point Bridge, the towers of Center City Philadelphia slide into view. After another mile, the Wells Fargo Center and Lincoln Financial Field appear on the left. To the right, the Navy Yard. Further north new buildings present themselves on the downtown skyline. Some I’ve read about; some are a surprise. My city, like a spurned lover, has moved on without me.

I take the Columbus Boulevard exit and make a left onto Washington Avenue, where the old immigration station used to be. After ducking under the I-95 overpass I begin the time-honored Philly sport of finding street parking. Living in Los Angeles has spoiled me. I live in an apartment complex with two (two!) private parking spaces beneath the building. I haven’t worried about finding a parking spot in nearly three years. Nor saved a freshly-excavated snowy parking space with a folding chair.

I turn right onto Front Street—nope, no spots—and then a left on Christian. Nothing. I drive up 3rd Street, make a left on Queen, then drive toward Christopher Columbus Boulevard and back up Washington. Finally I find a spot on Front in a two-hour limit zone. Which will become a free spot shortly (yes) but I’ll have to move by 10 a.m. tomorrow morning (fuck).

I hoist my bag from the trunk. The plastic wheels hit the pavement and roll up toward Christian Street. December winds are super-chilled by the Delaware River and blast through the blocks of the neighborhood. Back home in balmy California my 16-year-old son is just getting out of high school for the day.

Am I really here, doing this? And why, exactly? I’m not sure. Lately I’ve been operating by sheer instinct.

At the corner of Front and Christian is a neighborhood bar called For Pete’s Sake. Looks warm and inviting; this could be a contender. Whenever I travel somewhere I tend to find a home base, usually a bar, where I can have a quiet meal and a drink alone and just watch people. Some might consider this being a stalker; I call it being a crime novelist. The temptation to stop in for a drink right away is strong—and why not? I’m not going to be driving anywhere else tonight. And ever since the end of October I’ve been drinking heavily.

But first I’d better drop off my bags.

Half a block away from the bar is 107 Christian Street, where I find two young men weighed down with backpacks. They stare at the front door as if trying to puzzle out the magic spell that will open it.

“You guys here for the AirBNB?” I ask.

They confirm that yes, they’re tourists and have a room in this house. Heavy accents; Eastern European. Which strikes me as funny for several reasons.

“They sent me a code,” I tell them. “Let me try it.”

I punch in the numbers I was emailed. The door unlocks. Everyone is relieved, myself included. I hold open the doors for them. They file in, happy to have finally arrived at their destination.

If I were a more social animal—a proper journalist—I’d chat them up a little. Ask them what they were doing in town, where they were from. You know. Color stuff. But I am not in the right mental space. Why ruin the solitude of my despair? The backpackers shuffle down the hallway to their unit. My room is the immediate right of the front door. I punch in another code. The door unlocks with a click. I step into the darkness and fumble around for a light.

The place is more or less as described: one room with old wood trim, dark creaky floorboards. The bed takes up a good third of the room and is situated next to a bay window at street level. There are a few modern touches—Wifi, a projector that will let me watch TV on the wall. (I’ll never turn it on.)

The other half of the rental space is down in the basement, which is small and cold with a crazy low ceiling and an even lower support beam and vent. Everytime I walk down there—and there’s no choice, because the sink, toilet and shower are down there—I have to tilt my head sideways. (I’m 6’2”.) There is also a pool table, which sounded good in the listing, but to play I’ll have to tilt my body sideways. The shower is almost completely dark when you pull the curtain over.

But I chose this AirBNB for the location, not the amenities. I’m staying for three days on Christian Street in the former immigrant neighborhood that my family called home over 100 years ago.

It’s also where all of the murders took place.

Christian Street is cold and dark, almost nobody out. A few windows are lit up and I peer inside like a creep. Tastefully-decorated Christmas trees rest in tidy living rooms with grown-up furniture. In another life, I would have liked to have moved my family down here. I always loved downtown, and still regret moving to the Northeast after the kids were born. I would also like grown-up furniture.

If I were to walk you down Christian Street right now, you’d think: huh. No big deal. Another narrow street packed with rowhouses. But you don’t understand; you’re not seeing it in a historical context.

Christian Street was the main drag in a town that used to be called Southwark, one of the largest colonial settlements in the area—Philly’s O.G. suburb. Swedes landed there in the 17th Century and named two streets after their Queen (Christina), who ruled the Swedish Empire from the age of 18 until she refused to marry and was forced to abdicate the throne. Historians have described Queen Christina as a “lesbian troublemaker,” which makes her all the more awesome. They broke the monarch’s name in half and slapped on two different streets: Queen and Christian.

Everybody in Philly thinks “Christian Street” is a Roman Catholic thing. It’s actually a lesbian Swedish thing.

Southwark, a town just south of Philadelphia, was named after the town just south of London — which would eventually swallow it up. The City of Philadelphia didn’t get around to swallowing up Southwark until 1854.

(Note: If you wish to remain an independent town or municipality, I suggest a name other than “Southwark.”)

By the time my grandparents were born a century ago, the mighty town of Southwark had become an immigrant neighborhood, teeming with new arrivals looking for work on the nearby docks of the Delaware River. The Polish nickname for Southwark was Stanislawo, meaning the “neighborhood around St. Stanislaus Church.” This parish—like the town—technically doesn’t exist anymore, either.

Southwark is where both halves of my family began their lives in America.

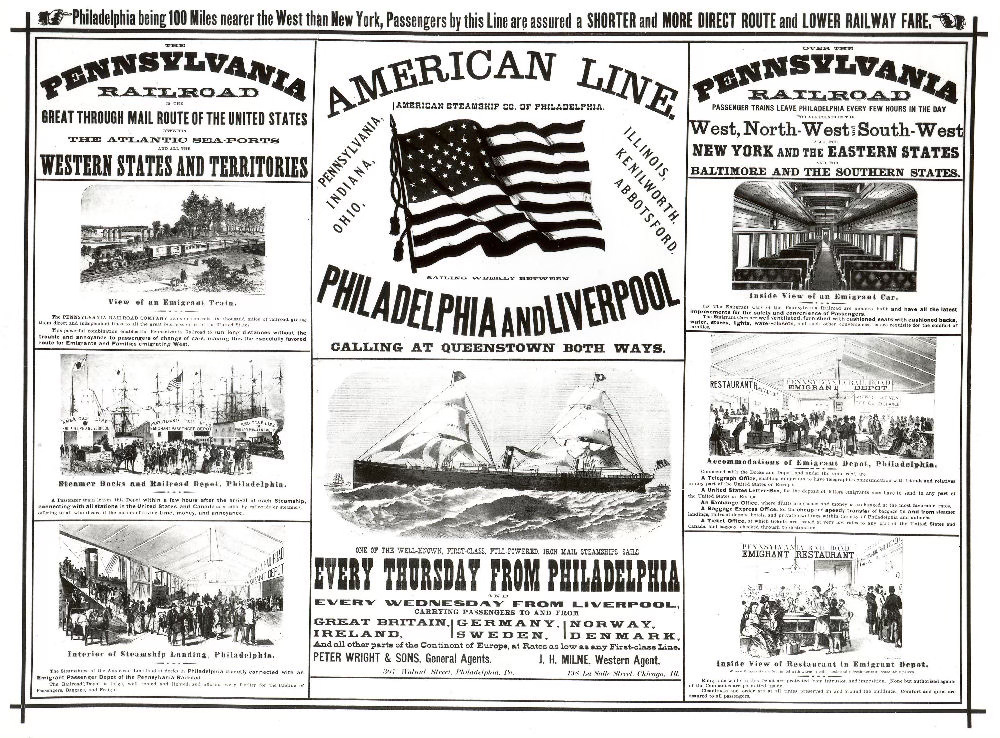

I owe my existence to the greed of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), which in the late 19th century was the most powerful business in the country. Think of it as the Amazon or Apple of its day. When PRR realized that Ellis Island was funneling immigrants to its chief competitor (the New York Central Railroad), they said not so fast, fuckers—and quickly built four transatlantic steamships and a shiny new immigration station at Pier 53 on the river.

Pennsylvania Railroad ads made the dubious claim that Philly was 100 miles closer to the West than New York City. I mean… sure. But the steamship voyage from Europe was also 200 miles longer. And the final 100 or so miles took immigrants up the Delaware Bay, where you could see plenty of land without setting foot on it. After a week-long, cramped journey in steerage, this must have been a special kind of torture. Especially when you’re stuck looking at Delaware.

Between 1887 and 1917, over one million immigrants would be processed through the Pier 53 station. The PRR’s lines would haul immigrants north, west and south—to cities for factory work; to rural areas for farm labor. Those who couldn’t afford the train fare settled in Southwark. I don’t know if they had any money or not, but my great-grandparents were among the ones who stayed.

My favorite noir novelist, David Goodis, set many of his bleak noir novels in Southwark and river wards like Frankford, where I was born and raised. Goodis did a lot of hanging out in these neighborhoods, even though he lived in the (then) upper-middle class enclave of East Oak Lane, miles away from the Delaware.

Southwark was dealt a harsh blow in the 1950s when city planner Edmund Bacon—that would be actor Kevin Bacon’s father—decided to ram I-95 through the eastern edge of the neighborhood. Three hundred historic buildings were razed. When they destroyed all of those structures, the ancestral Swierczynski rowhome was right on the edge, spared destruction by just a few dozen yards. I’ve walked those yards, looked down at I-95 below, cars whizzing by in both directions, with practically zero degrees of separation.

Southwark ceased to exist in 1969, when realtors took the northern chunk of the former municipality and renamed it “Queen Village.” The southernmost portion became known as Pennsport. Only a few traces remain. There is a restaurant called Southwark that specializes in swank cocktails. There was a notorious housing project called Southwark. And there used to be the Southwark Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia—where I did my very first reading as a fiction writer, oddly enough, at the tender age of 17—but they later renamed it after a politician. By the time I arrived on the scene in 1972, Southwark was distant memory, mentioned by absolutely no one in my family.

And here I was on Christian Street, making up for lost time.

My blood has changed after nearly three years of living in California. Not to put too fine a point on it: I’m fucking freezing. I wish I’d packed a hat, especially since my head has been shaved bald since August. I could also very much use a beer or three after the long haul from L.A. But I feel compelled to head straight to the scene of the crime. So I keep walking west on Christian Street.

By the time I’m crossing 7th Street my heart is racing. It’s not from the cold. I’ve visited this crime scene before, but now I know a lot more about the dizzying series of crimes that took place in this tight, geographic location. It’s hard not to keep my novelist brain from projecting violent images onto the quiet city streets.

Like drive-by killings of two men on Eighth Street, just below Christian.

Or the violent shoot-out that happened on the 800 block of Christian, all while children were headed to school.

A century ago, the block of Christian between 8th and 9th was known as Dope Row. The block between 9th and 10th was Murderers’ Row. A few blocks away was the “Bloody Angle,” where Passyunk slashes across Washington Avenue.

Yeah… lots of killing.

All of this bloodshed will figure in the story you’re about to read. But primarily, I’m here to visit the pizza shop at the corner of Ninth and Christian because of what happened nearly 100 years ago.

Let me just give you the straight facts, because we’re going to unpack this in much more detail later.

On March 20, 1919, Patrolman Joseph T. Swierczynski was walking his beat when he heard a ruckus. Four hoods were holding up a black guy near the corner of Ninth and Montrose. As Swierczynski approached, the four hauled ass down to William J. Beine’s saloon at the corner of Ninth and Christian at the top of the Italian Market. Swierczynski yelled into the bar, ordering them to come out and surrender. Instead, one of the hoods stepped outside, opened fire six times.

Patrolman Swierczynski was struck twice—once through his chest, once on his left side. He collapsed and bled out on the tiled entrance of the saloon. The hoods fled the bar through a side door.

Contemporary newspaper accounts vary, but according to the Philadelphia Bulletin, Swierczynski lay there bleeding and alone for a half hour before an anonymous woman finally contacted the police station at 7th and Carpenter streets. The hoodlums, it seems were members of the Black Hand—and nobody crossed them. Not down here.

By the time police arrived, Joseph T. Swierczynski was dead, leaving behind a wife and two young sons. He was only 27 years old.

The killing partially inspired my tenth novel, Revolver, even though it was set in a completely different era (the 1960s) and played out in a very different way. The original story, and the aftermath, remained untold until now. That’s why I’ve flown here. To tell the real story, best as I can from the other side of a century. My idea was to drop off my bags and walk straight down to Ninth and Christian streets to have a slice of pizza inside the former saloon where a Swierczynski murdered.

Walking the streets featured in my books has become a vital part of the process. I don’t like writing about a place I haven’t experienced.

My first novel, Secret Dead Men, was written in Brooklyn but was all about being homesick for Philly—specifically, the Philly of my youth in the 1970s. Novel number two, The Wheelman, came about after I spent way too much time casing my actual bank branch at the corner of 17th and Market in downtown Philly. (This was for an introduction to a nonfiction history of bank robbery; when I couldn’t get the caper out of my brain, I pulled a fictional version.) The Blonde was born on daily commutes on the Frankford El, and Severance Package was set at the former Philadelphia Magazine offices at 1818 Market. I intentionally set the action at 1919 Market, which for a long time was a vacant lot, just in case anybody went to see it. (Spoiler: the building burns down in the novel, and I hoped at least one reader would think: Holy shit!) Expiration Date was my detailed recreation of Frankford. Even when I escaped Philly with the Charlie Hardie trilogy, the action was inspired by family road trips to Los Angeles and San Francisco and various points across the country… and the story ended up back in Philly anyway. By the time I was writing Canary and Revolver, I doubled down on my local research and explored novel locations as if I were still a journalist. I like grounding my stories in actual places.

This is what brought me back to Christian Street. I want to tell the story of the rise and fall of the gangster who killed a relative of mine. I’ve wanted to tell this story for years now, and a recent tragedy has given this task some fresh urgency. I wanted to tell this story before I lost my mind completely.

Also, after a long flight from a city that has notoriously lame pizza, I was craving a decent slice.

As I approach the corner of 9th and Christian, however, all I see is darkness. What’s the deal? It’s a Tuesday evening in December, not a holiday. I seem to remember the Italian Market buzzing with activity at all hours.

But no, the pizza joint at the corner of Ninth and Christian is sealed under metal shutters. Please, please, please don’t let this place be closed forever. It was open just a few years ago…

Okay. Not closed forever. Just for the evening.

I’ll have to return for a slice of death pizza tomorrow.