A Polack Walks Into a Bar

Man Full of Trouble (Chapter Six): The Bluecoat's Beat; "I'm Gonna Knock That Guy Off"; An Urgent Telegram from Atlantic City

This is the sixth installment of my pulp non-fiction gangster memoir, Man Full of Trouble, detailing the rise and fall of the criminal who killed a family member 100 years ago. Comments and questions are welcome; huge thanks to the paying subscribers funding this book. Today’s chapter is a special one: March 20 marks the 106th anniversary of the murder of Joseph T. Swierczynski.

Joseph T. Swierczynski joined the Philadelphia Police Department in late April 1917. His salary: $2.50 a day.

Being a cop then is not like being a cop today. For one, they’re weren’t referred to as “cops.” They were “bluecoats,” a reference to their uniforms. There was no police union. There are no forensic labs.

There are, however, ward leaders. Ward leaders are controlled by the Organization; the police, in turn, are controlled by the ward leaders.

Joseph T. was attached to the Second and Christian streets station, which covered the Third Ward, a fairly narrow strip of land stretching from the Delaware River to Broad Street. The northern boundary is Fitzwater Street, with Christian Street on the south. It’s a rectangle, two-tenths of a mile high and about a mile-and-a-half wide. Below it is the Second Ward; above it, the Fourth and Fifth. They’re river wards, teeming with immigrants literally fresh off the nearby boats.

Just like the Swierczynskis, at the turn of the century.

The day Joseph T. joined the force, he was 25 years old with a young wife and son. I don’t know what kind of work he did before he became a cop. Joseph T. lived just a few blocks away from his station house at Second and Christian, barely a five-minute walk. His neighborhood was his beat.

Joseph T. was my grandfather’s first cousin, but they were born more than a quarter century apart. By the time Joseph T. was a few months into walking his beat, my grandfather was the new Swierczynski baby who lived a few dippers down the street.

Maybe Joseph T. held my infant grandfather in his hands — just like my grandfather once held Infant Me in his arms.

I like to think about that connection, as tenuous as it may be.

Officer Joseph T. Swierczynski was kept busy. His beat was crawling with stick-up men and burglars. The Great War attracted a lot of men to the munitions plants. When the war ended, the men were suddenly out of work, so they sought alternate sources of revenue.

By late January 1919 the Philadelphia papers were reporting a major crime wave—$300,000 in stolen loot since the first of the year. Three hundred robberies; 80 hold-ups. Businessman William Goodis reported his automobile stolen from the vicinity of Second and Chestnut, one in a long series of auto thefts. (His two-year-old son David will grow up to write crime novels like Black Friday and Shoot the Piano Player.)

There was a city-wide cop shortage; even a wave of hires in early March 1919 wouldn’t be enough.

The fringes of Joseph T.’s beat bumped up against the Italian Market. Once you crossed Christian, you’d be in the next police district.

You’d also be walking along the edge of a tinderbox.

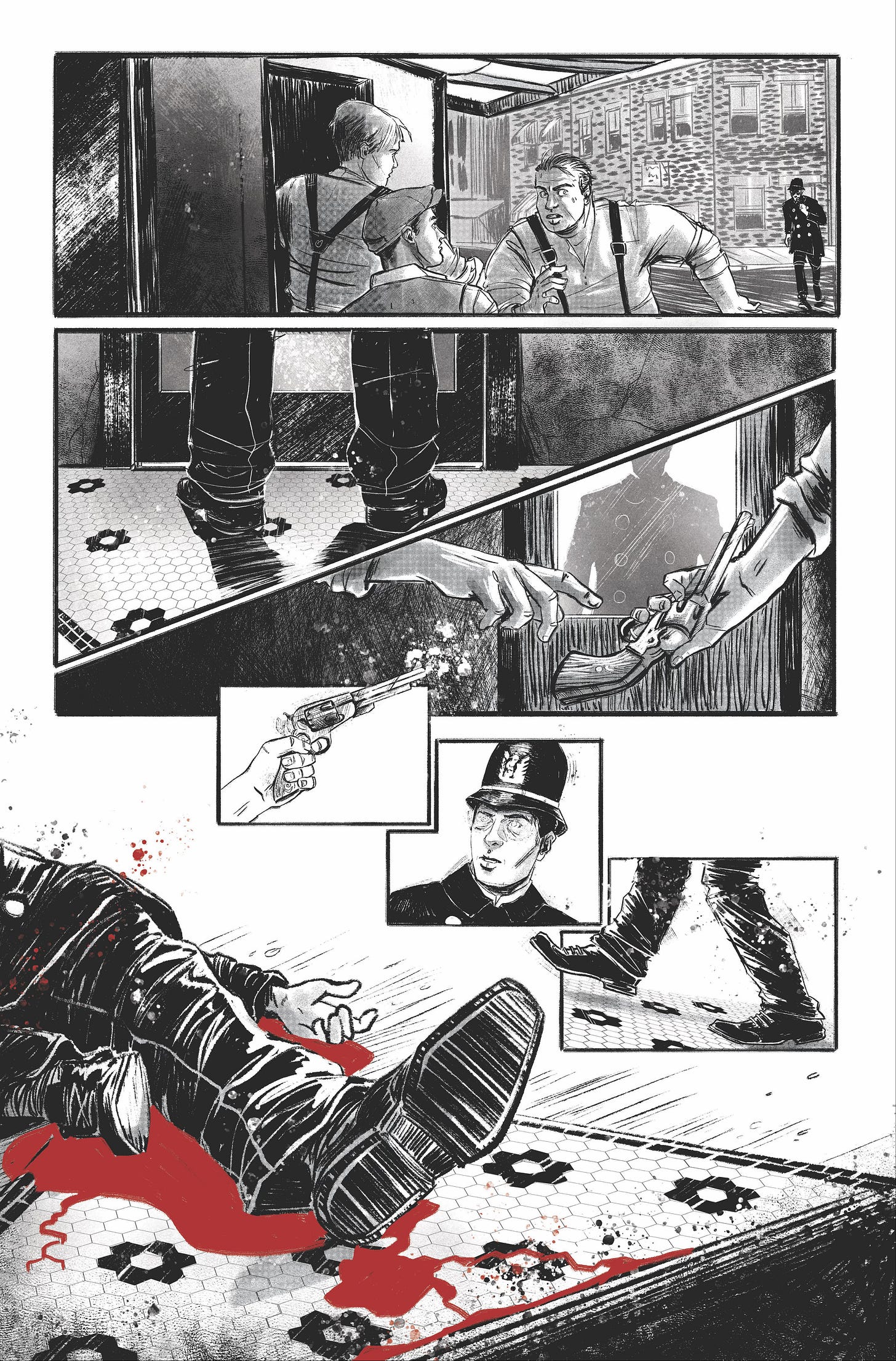

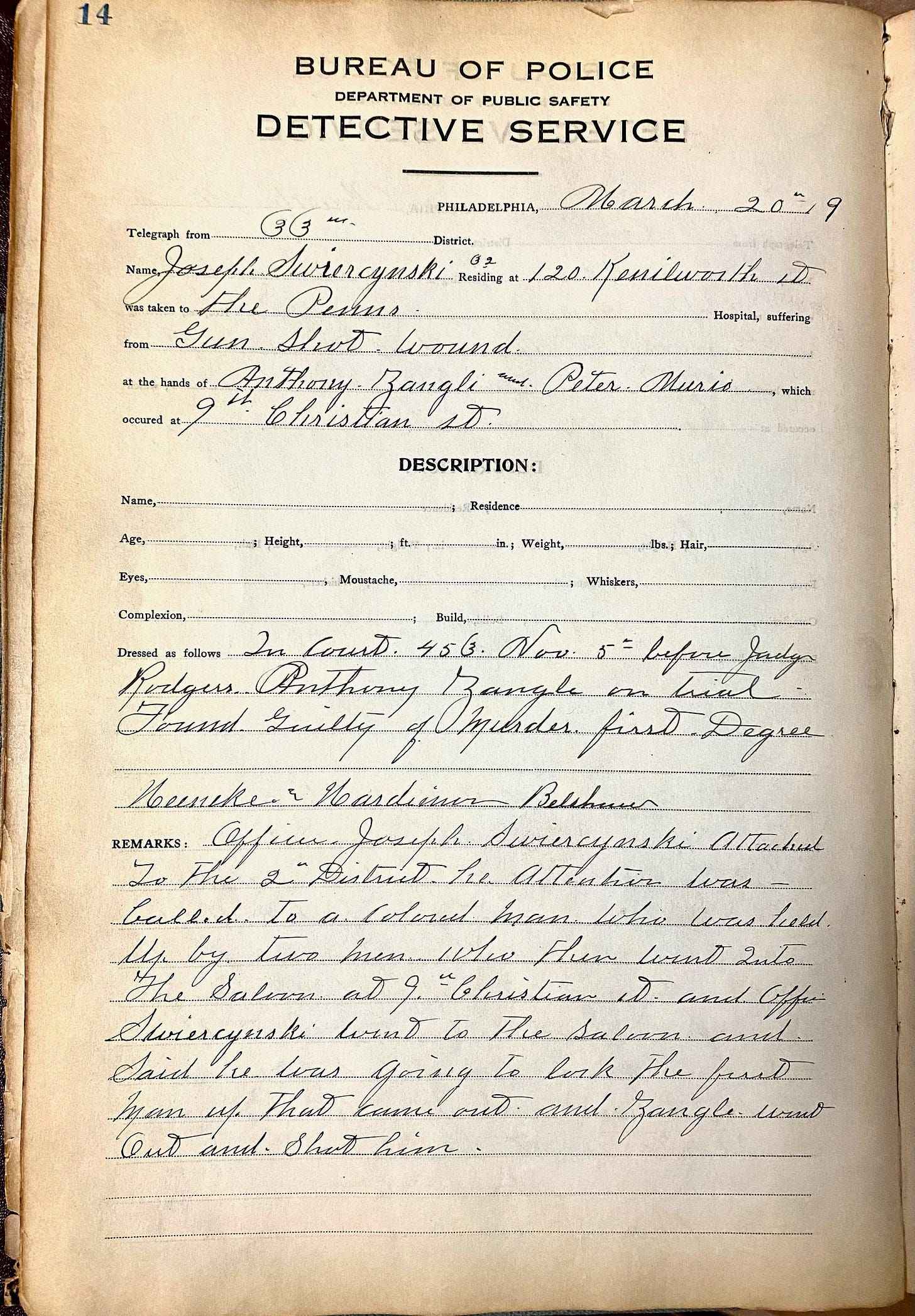

On the night of March 20, 1919, just before 10 p.m., Patrolman Joseph T. Swierczynski was approaching 9th Street from Catharine when he happened upon some hoodlums mugging a black guy.

Back then, 9th Street was the uneasy border between working class Italian-Americans and African-Americans. Maybe the mugging victim decided to cross the street, breaking the unspoken rules. Maybe he was minding his own business.

Swierczynski recognized the hoods. They were notorious drug pushers and neighborhood muscle for hire.

The hoods recognized Swierczynski, too — and bolted down Ninth Street, taking refuge in a criminal-friendly saloon at Christian.

Joseph T. stopped short of the entrance, stood on the green-and-white tiled entrance, and shouted into the saloon:

“It’s bad enough to sell dope around here without holding people up! You had better stop it!”

(This is the only quote attributed to Joseph T. that I’ve ever found. It was told to a journalist by a witness inside the saloon.)

Meanwhile, inside the saloon, one of the hoods told his pals:

“I’m gonna knock that guy off.”

And he did.

The hood stepped out of the saloon doors, gun in hand. Joseph T. took a step back. The hood opened fire six times.

Moments later, Joseph T. was on top of those green-and-white tiles, bleeding out.

A crowded gathered around the body. Nobody called the police.

“It is presumed that if Swierczynski was noticed during the period he lay before the door of the saloon,” wrote a reporter from the Philadelphia Public Ledger, “the residents of the neighborhood were too frightened to notify the police.”

At 10:07, a call from a “mysterious woman” reached the police station at Seventh and Carpenter. “When the woman telephoned,” according to a Philadelphia Bulletin reporter, “the house Sergeant undertook to get her name but she hung up the receiver.”

Finally police from the Seventh and Carpenter streets station stepped into the saloon. Behind the bar was William J. Beine, proprietor. With him was Frank Cooper, a regular, who was asleep at the bar. Beine told police he heard the shots, but didn’t bother to investigate.

According to the Evening Public Ledger, Joseph T.’s body was carried to Pennsylvania Hospital. The attending physician said that death was instantaneous, and “five bullet wounds were found in his arm, chest, leg, knee, shoulder and back.” But the Philadelphia Public Record claimed only two bullets struck the police officer—”one through the chest and one through the left side.”

Three material witnesses were taken into custody: saloon manager James Hughes, janitor Frank Cooper, and patron Manuel Dice.

Locals in the know weren’t surprised by the killing. “Swierczynski, it is said, was known as a foe of the Blackhand [sic],” according to the Public Ledger, “and had made numerous arrests of men allied with that coterie … He leaves a wife and two small children. Mrs. Swierczynski was ill when news reached her last night of her husband’s death.”

The next day’s headines:

Policeman found murdered at entrance to a saloon

FELLOW OFFICERS RESPOND TO TELEPHONE CALL AND DISCOVER SWIERCZYNSKI’S BODY

Mysterious Phone Call Tells Policeman’s Death

WOMAN’S VOICE TELLS POLICE OF MYSTERY CRIME

Answering Phone Call, Patrolmen Find Brother Officer Murdered

MEN IN BEINE SALOON HELD AS WITNESSES

Six Shots Said to Have Been Fired; Two Hit Dead Man

A century later, it’s unclear. What I do know comes from the fragmentary reporting of local journalists. They asked questions. They wrote down what they were told. They phoned the facts in to the copy guys. The copy guys turned what they were told into a series of sentences, which was quickly edited and set into type and published hours later.

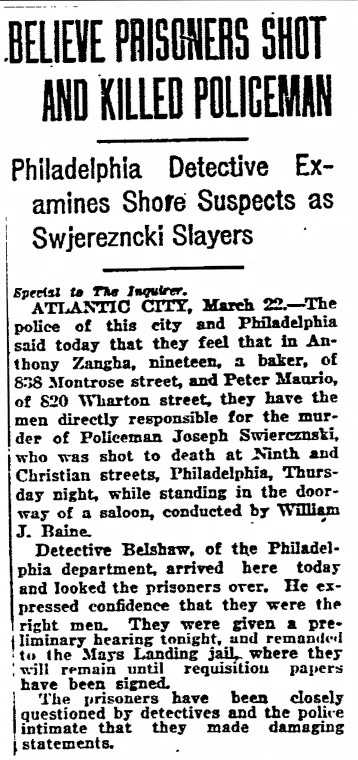

By Saturday, a description of the killer was released via telegraph. Twenty minutes later, Atlantic City Police responded with a telegram to Captain Souder of the Philadelphia Police Department that they had detained a suspect: 19-year-old Anthony Zanghi.

Zanghi had a hundred bucks on him, but no gun.

Zanghi claimed he worked for his father, who was a baker. He was also a chauffeur, employed by barber Frank D’Amato. Zanghi’s wife Anna was ready with an alibi. She told reporters they attended an Italian ball the night of the murder, dancing well past midnight. Then on Friday, they traveled to Atlantic City to visit an aunt, Mrs. Anna Latore, who lives on N. Mississippi Avenue.

Nonetheless, Philadelphia detective Belshaw traveled to Atlantic City and “expressed confidence that they were the right men,” according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. By Sunday, Anthony Zanghi had been transported back to Philadelphia and sent to Moyamensing Prison, where he’d await his trial.

According to the Philadelphia Bulletin, “[Zanghi] insisted he had nothing to do with the shooting.”

That's so unfortunate. Just a guy out there doing his job and fighting the scum and he gets gunned down for his efforts. This was very told. I was pulling for him but sometimes things don't work out, especially in true crime. Awesome story, Duane.